THE MAP MAKERS - FROM AIRFAST NEWS 1972

The Division of National Mapping's contract for 1971 commenced on 17th May at Halls Creek, W.A., and concluded, 400 flight hours later, at Rockhampton, on 28th September.

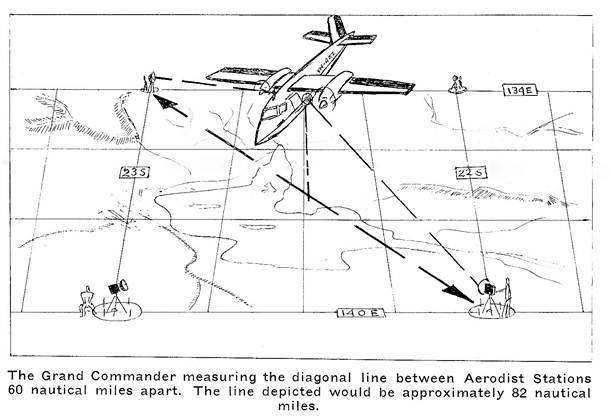

During the last few years, the Division has undertaken the mammoth task of establishing Aerodist (Aero distance measuring) Stations throughout the remote areas of Australia. To determine the location of a station, the surveyors calculate, as accurately as possible from an aerial photograph, the exact intersections of whole degrees of latitude and longitude. This puts a station every 60 nautical miles. (Except on state borders, where 30 mile stations are established for more accurate control of the boundary.) The initial station was established with reference to a trig point of known position and the purpose of this vast chain of subsequent stations is to provide accurate datums for the correlation of a continent-wide mapping system.

The Aerodist station consists of a peg cemented into the ground and numbered. Four protective steelposts are positioned around the peg and a circular trench or, in rocky ground, a circle of white painted stones surround these to aid identification from the air.

Initially, the helicopter's task was to position the Aerodist remote parties at their stations, from which the measurements are taken. When these personnel are in position, spread out over thousands of square miles of desert, a Grand Commander, fitted out with complex electronics equipment, flies between the points, recording the distances on a graph. After the measurements are taken, the Commander then spot-photographs the points, so that their exact location can be established on the earth's surface.

Navigating the Desert

Depending on the location of the helicopter support camp, the pilot is faced with the problems of navigation over remote and uninhabited areas, distance, endurance, maximum weights, and often, high ambient temperatures. Generally, the weather conditions are fine, but at times, dust and smoke haze reduce visibility.

The daily flight plan can include transporting personnel, camping equipment and survey apparatus to points over 120 nautical miles from the camp; sometimes having to return via a fuel dump many miles away, and then fly to another station to shift the party to a new location. The demand on the pilot and helicopter is high, and it is not unusual to fly between 500 and 800 miles a day.

The key to the operation is flight planning, and the practised use of all aids available. To navigate the desert to a peg in the ground requires an experienced and logical approach to the problem. However, demanding as the navigation is, the problem of endurance versus weight is the over-ruling consideration and dictates the flight plan.

An essential requirement is a careful and realistic study of the programme, days or, sometimes, weeks in advance. The pilot can estimate his fuel needs in relation to the loads he is to carry and the distance to be flown. He can then position 44 gallon drums of Avtur in various suitable locations throughout the desert. Sometimes, this can be done when the helicopter is traveling empty to shift a remote party from one point to another, but at other times, flights have to be made especially for this purpose.

Needless to say, the pilot must note carefully the location of his fuel, as he may return to the dump from a different direction, weeks later and require fuel after several hours flying over the desert.

Every assistance is given to ensure that the flights proceed as smoothly as possible. Most stations are in the corners of map sheets and so composite maps, consisting of sections of the four maps covering the corner, are joined together to give the pilot the overall terrain, without having to juggle four large map sheets. Each remote party is supplied with a radio which gives the pilot the advantage of receiving homing directions from them (providing the helicopter is close enough to be seen or heard), should he require assistance in locating an occupied station.

The 'Map' Men

About sixteen men from the division form the mapping crew and they are split into two parties. The centre party (consisting of the OIC, several airborne aerodist operators and an electronics technician) operates from a suitable airfield with the Grand Commander and the remainder work from the helicopter support camp, which could be situated over 100 miles away, depending on airfield availability and the area to be measured.

From the helicopter support camp, two men of each remote party are positioned in the field, where they can remain for hours or days, depending on their location in the overall plan and the progress of the programme.

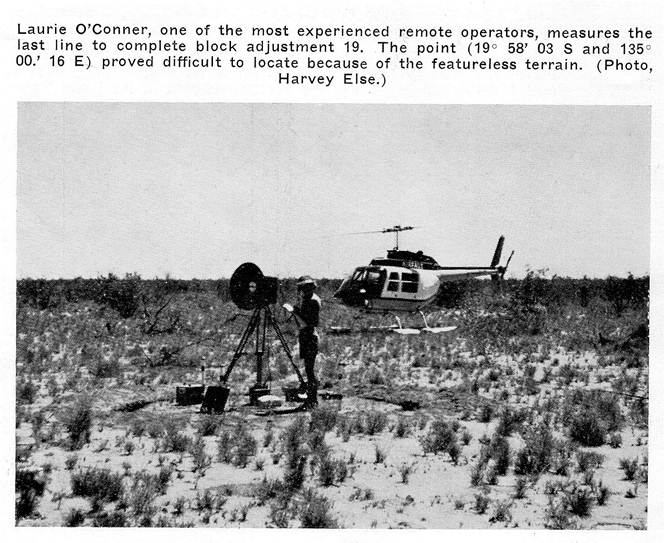

Four of these parties are usually located in the field at the same time. In addition a "Helicopter stand-by remote party", consisting of the operator, measuring equipment and survival supplies, works isolated points further a field, such as the odd corners, or extra out-of-the-way stations in the block adjustment. As the name implies, the helicopter "stands - by" at these points while the measurements are taken, and then moves on to another point.

Living in the Desert

The nature of the operation and the terrain make it essential that camping equipment is kept to a minimum. Men, equipment, water, fuel for both aircraft and trucks and supplies often have to be transported by vehicle over long distances and into almost inaccessible areas. The luxuries of living, therefore, are low on the priority list. It is not unusual to live on a water ration, eat out of cans, sleep in the open and go without a wash for many days. From experience, you learn to shake out your sleeping bag at night, and tip out your boots before putting them on. Snakes, scorpions and centipedes seem to have an attraction for these homely spots. However, a season with the ‘map’ will always guarantee you one health benefit - you will lose weight. (With due respects to the chefs in the field.)

While the support camp can afford to be somewhat selective in their camp-site, the men on the aerodist station are compelled to take what comes. They could be located amongst sand dunes, burnt-out scrub or in a dust bowl and the nickname, 'Desert Rats', is justified. The isolation and the months of living under these conditions takes its toll of the crews. Most of the remote parties are single, young men but they usually only stay for two or three years.

(Helicopter Utilities Pty Ltd's representation on the 1971 contract was one helicopter with pilots Harvey Else and Brian Harriss and Engineers Jack Fackrell, Frank Summers and John Moore. This article was contributed by Harvey Else, who started the contract at Halls Creek, W.A., and after relief in the middle, completed it at Rockhampton.)