THE

DIVISION OF NATIONAL MAPPING’S

GEODETIC

SURVEY OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA –

A

PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE

by

John Allen and David Cook, October 2009

Introduction

In

April 1974 the Directorate of Overseas Surveys, Great Britain, wrote in their

Information Services Newsletter, “The Australian geodetic network, a great deal

of it completed in ten years, must always be historically one of the survey

wonders of the world”.

Although

this statement of recognition was primarily directed to the vast geodetic

network within the Australian continent, geodetic control was also extended

into Papua New Guinea (PNG) where surveying teams faced vastly different

conditions and challenges to those experienced within Australia.

This

geodetic survey of Papua New Guinea was a joint operation by the Royal

Australian Survey Corps and the Division of National Mapping. The Army's

responsibility was to establish survey control around the coastal perimeter,

and the Division’s to establish geodetic control throughout the mountain

ranges.

For

the first time in their field operations, helicopters were used by the Division

to position survey parties on the selected mountain peaks that ranged in altitude

to nearly 15,000 feet. In a well planned and coordinated operation, albeit one

of high risk, the geodetic survey was completed in four years.

Shortly

after the conclusion of the work, a report entitled “The High

Level Geodetic Survey of New Guinea (Technical Report No. 8, March

1969)” was written by the Division’s Supervising Surveyor, H.A. (Bill) Johnson,

but had a strictly technical focus.

As

this particular survey was so unique, the Authors, as members of the PNG

geodetic survey party, have compiled this paper to ensure that the personal and

other aspects of this important work is not overlooked or forgotten. In

addition, the Authors pay tribute to all our National Mapping colleagues, as

well as those from the Royal Australian Survey Corps and the PNG Department of

Lands Surveys and Mines who assisted on this survey because it truly was a team

effort.

Imperial

units of feet (ft), pounds and ounces (lbs, ozs) are retained as these were the

measurements of the time.

Background

to the High Altitude Geodetic Survey of PNG

For

many years Australia had a special relationship with Papua New Guinea (PNG or

sometimes TPNG for Territory of Papua and New Guinea).

In

1904 the Commonwealth of Australia began administering British New Guinea,

which was the southern half of the partitioned island, and in 1920 Australia

assumed a mandate from the League of Nations (predecessor to the United

Nations) to govern the northern half, formerly known as the German Territory of

New Guinea. It was administered under this mandate until the Japanese invasion

in December 1941 brought about the suspension of Australian civil

administration.

After

World War II, the two territories were combined into the Territory of Papua and

New Guinea, which name was simplified later to Papua New Guinea, and Australia

continued its administration overseen by the United Nations.

The

war years had revealed the inadequacy of reliable mapping in PNG. During those

years there was little opportunity to rectify this, but as early as 1942 and

1943, H.A. Johnson, then an officer in the Australian Army, was able to

reconnoitre parts of the country. Whenever possible, courtesy of the United

States Air Force, he obtained flights over the mountain ranges with a view to

identifying possible mountain peaks to form a geodetic framework. He also

gained first-hand knowledge of the physical difficulties on the ground that

would be encountered when beaconing those peaks. However, with the cessation of

military survey activities in 1945, the commencement of a geodetic survey over

PNG lapsed into abeyance.

In

July 1958, at the request of the Administrator of PNG, for advice on how best

to satisfy their serious mapping needs, the Director of National Mapping, B.P.

Lambert flew to Port Moresby. He attended conferences of the Technical

Committee on Photogrammetric Mapping and made a wide aerial reconnaissance of

the area to form an appreciation of the requirements.

A

fundamental conclusion was reached being that a proper geodetic framework was

required over PNG as soon as possible, and that the framework should be

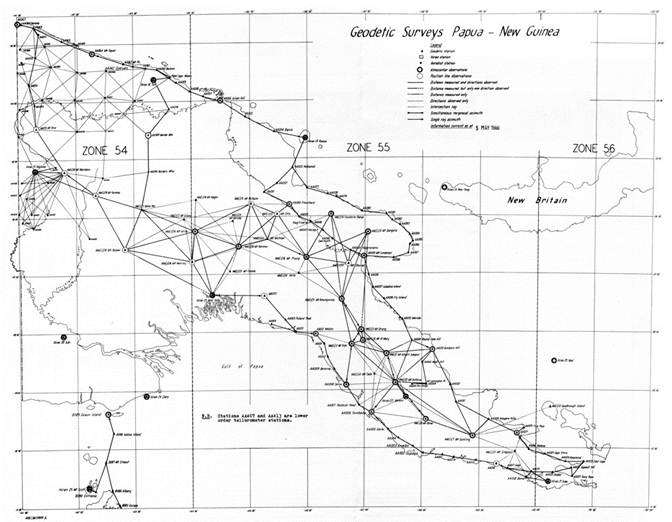

connected to the Australian network. Following that conclusion, two main traverses

were planned – one around the coastline (low) and another along the central

ranges using the major peaks (high), with selected connections between these

high and low surveys. Annex A contains a general map of PNG circa 1969 while

Annex B shows the High and Low Geodetic Net.

Original

Mapping

In

1961, at the commencement of the Division of National Mapping’s (Natmap) work

in PNG, most maps of the vast interior of the country were sketchy. Mountain

peaks had been identified but heights and positions were approximate or

incorrect. Maps of the ranges west from Mt Hagen to the West Irian border were

a collation of sketches of indeterminable scale that depicted mountains of

somewhat random shape and height.

As

an example of this unreliability, Mt Suckling in the south-east was originally

fixed by Captain Owen-Stanley early in the 19th century by compass bearings

from his boat as he sailed around the eastern end of the island. However a patrol officer’s report in the 1950s related that,

while working along the north coast, he had climbed the mountain on a Saturday

morning in cloudy weather and that it was 15 miles closer to the coast and

lower than the map showed. This notification was classified as a reliable

report and was sufficient to cause Mt Suckling's position on the map to be

changed. When beaconing was carried out by National Mapping’s Technical

Assistant, Guy Rosenberg in July 1962, his astronomical (astro) fix confirmed

the original position determined by Captain Owen-Stanley as being correct, and

this was later verified by an astro-fix at Mt Simpson and an azimuth

observation to Mt Suckling ‘s beacon. (Guy Rosenberg's ascent of Mt Suckling

was a little more arduous than the Saturday morning climb that gave credence to

the mapping error. It took Guy eight days to climb from Safia, plus two days to

build rafts and cross the Adau River and five days to return).

Other

mapping errors included Mt Albert Edward shown 2,000ft above its actual height,

but the most serious heighting error was that of Mt

Kenevi, just to the east of the Kokoda Gap in the Owen Stanley Range. This peak

had been wrongly identified and given a height of 8,487ft, when it was actually

11,315ft. Five wartime wrecks lie around its slopes at heights above that shown

on the original maps. One of these wrecks was that of an Avro Anson, LT294,

that crashed on 30th January 1944. Killed were Group Commander

Frederick Wight, the most senior RAAF officer to go missing in WW2, and Wing

Commander Keith Rundle. Shortly after the erroneous height of Mt Kenevi had

been discovered during Natmap's survey, the remains of the two airmen were

recovered and buried at Bomana War Cemetery on 5th March 1965.

It

may seem incredible that mapping errors such as these would not have been detected

prior to the arrival of the geodetic surveying team. For those most likely to

be affected by such errors, however, the commercial pilots of PNG did not

depend upon map accuracy as they were trained using visual flight procedures.

Trainee pilots had to fly five times along any route under the supervision of a

senior pilot before being cleared for solo commercial flights. Consequently

fixed-wing pilots all knew their way around the country without using maps and

the misplacement of Mt Suckling and the incorrect heighting of Mt Kenevi, (and

probably many other peaks), were not major problems. Light aircraft never flew

in cloud, and instrument flying was not used. Unfortunately

wartime pilots had flown under different rules and conditions, often with

tragic results.

The

commencement of surveys as a basis for accurate mapping in this region were

undertaken in the middle to late 1950s as Project Xylon and Project Cutlass.

The Royal Australian Survey Corps and the United States Army Corps of Engineers

combined in ship-shore triangulation surveys around the coastline of New

Britain and the islands of New Ireland (Coulthard-Clark, 2000). It should also

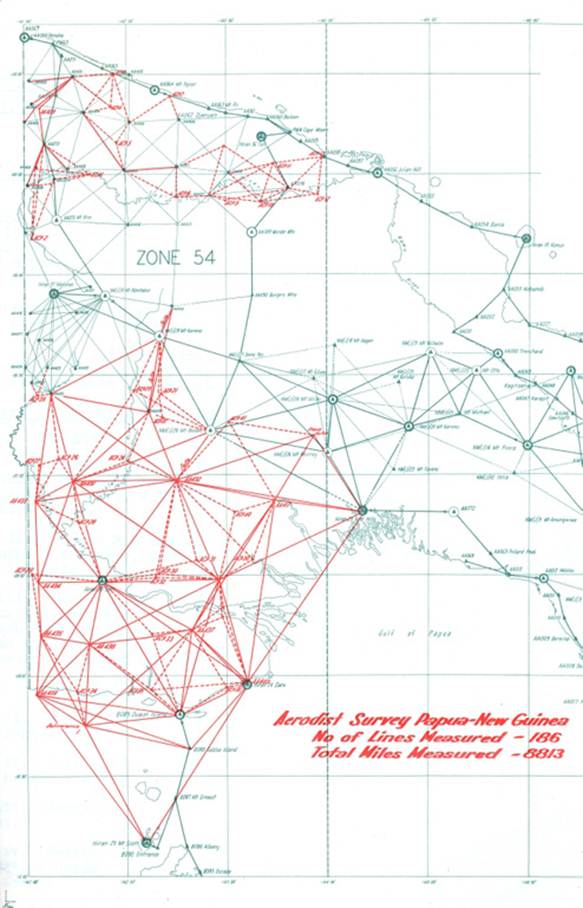

be noted that the Army undertook Aerodist (AERO DISTance measuring) operations

in the western region of PNG. Refer Annex C.

Later,

almost in parallel with Natmap’s work, during the period September 1962 to June

1964, another, more extensive survey operation was also underway, that of the

United States Southwest Pacific Survey. The aim of that survey was to establish the principal islands of

the Southwest Pacific area on a common geodetic datum using HIRAN (HIgh-precision

shoRAN).

To complete the story, Australia through National

Mapping was involved with the joint Indonesian and Australian Survey of the border

between the Territory of Papua New Guinea and West Irian in 1966/67.

The

Start of the Survey – Reconnaissance and Beaconing

H.A.

Johnson's personal experience in PNG in the 1950s and 60s gives an introduction

to what lay ahead for the beaconing parties. He wrote:-

“Papua

New Guinea lies between the latitude band of 2 to 11 degrees south and

generally receives more than 100 inches of rain annually. Such rainfall has created

dense tropical vegetation over most of the land, with great river swamps and

deltas. The country is geologically young and unbelievably rough – Mt. Wilhelm,

the highest peak stands at 14,800 feet. Many other mountains along the spinal

ranges are over 13,000 feet and are mostly interconnected with ridges and spurs

so steep and knife-edged it would seem that only a mantle of vegetation holds

them in place. At times of continuous torrential rain, rock falls and mud

slides are common. The few vehicular roads, many of them only suitable for

4WD's, often become blocked and bridges can be washed away. From the air, the

lower slopes that lead to the main ranges look deceptively smooth with

accessible grades, but on the ground the reality becomes a fascinating and

challenging new world of a silent, dripping, half-lit tangle of slippery roots,

spiny vines and bushes, with many buttressed trees festooned in moss. Progress

through this labyrinth is difficult and frustrating, as often long steep climbs

are negated by descents of similar magnitude before the next ascent begins.

Climbing out of the heat and humidity of the rain-forest, and leading up to

11,000 feet, the vegetation and terrain becomes less hostile, and pressing on

to higher elevations stunted beeches make way for alpine grass and then to bare

crags. These then were the majestic peaks, towering over myriad jungle clad

valleys and ridges, that became the goal of our reconnaissance and beaconing

parties.”

The

work of beaconing was undoubtedly the most physically demanding aspect of the

survey, but much satisfaction was derived in establishing each trigonometrical

(trig) point. Those involved knew that not only would the beacons mark the

origin and authenticity of all future geodetic and cadastral work, but would

also remain as permanent monuments for as long as nature and importantly man,

allowed.

In the following section

David Cook recalls some of his experiences

Appointed

by Natmap as PNG Resident Surveyor for the Geodetic Survey, I arrived in Port

Moresby in 1961 with my young family.

Widespread

cooperation and assistance would be instrumental to the success of the survey

necessitating good personal contacts with PNG Administration Departments,

commercial entities and others in the private sector, and also missionary

organisations. To help in this work a Frenchman, Guy Rosenberg, was also

transferred to Port Moresby from Australia.

In

developing a strategy to commence the work, the most important contacts were

people whose work had taken them into the mountainous regions where our work

was to be undertaken. As well as help from PNG District and Patrol Officers,

Catholic Priests in the Goilala area north of Port Moresby were able to give

assistance as some had climbed five of the mountains that were to be included

in the survey. All the advice was most helpful, particularly about a climbing

route for the almost precipitous, 10,750ft, Mt. Yule.

In

July 1959 beaconing for the high level survey

commenced on mountains near Port Moresby.

Selection

of Peaks for Beaconing

The

first step in beaconing the central mountain chain was to fly to the highest

peaks to check which were intervisible and select a succession of them to

establish the central traverse. Then, having made the selection, another aerial

reconnaissance of possible climbing routes was necessary. For example, the

south face of Mt Suckling was observed to be all steep landslips and falling

stones, dictating a route along a narrow ridge. Some peaks were going to be

very difficult, such as Giluwe with a huge, vertical sided rock on the summit,

and Mt Victory which turned out to be impossible, having a large high rock on

the summit that towered above surrounding thick forest with enormous trees.

However, the major deterrent for beaconing this peak was the fumerole at the

highest point exuding a steady flow of volcanic gas. (Mt Victory is only 50

miles from Mt Lamington which had erupted unexpectedly and violently in 1953

and caused some 3,000 deaths).

Hills

below 10,000ft were mostly heavily timbered and were required to be climbed on

foot and cleared, and some hills such as Wamtakin and Obree, needed a wooden

landing pad to be constructed to provide a safe landing for the future use of

helicopters. Some were too heavily timbered to be cleared, such as the highest

point on Goodenough Island, climbed by Guy Rosenberg, where trees were three

feet in diameter.

Once

the aerial reconnaissance of each peak had been made it was necessary to

contact the nearest District Office. All the Patrol Officers and District

Officers were consistently helpful with assistance regarding access routes,

recruitment of carriers, storage of cargo flown in before the climb, any

serious obstacles, and providing guidance on dealing with the local people as

some customs varied from one place to another.

Recruitment

of Carriers

A

climb, to the peak to be beaconed, generally started from the nearest Patrol

Post where, between 60 and 100 carriers were recruited, depending upon the

distance to be covered and their availability. Daily wages were set by the

local District Officer and clothing and personal equipment were provided to

each carrier. This consisted of a warm shirt, rain cape, blankets, eating gear,

and waterproof bag to carry them plus a mandatory food allowance including 1lb

of rice and 4oz of tinned meat per day. The maximum load per man was 40lbs and

the effective payload diminished by the day. Two crowbars for digging out rocks

for the cairn plus sleeping gear and a couple of day’s food

made up a 40lb load.

Most

of the walking was above the highest habitation or beyond where local food

might be purchased. Tents for 50 or more people, steel beacon poles, vanes, guy

rods and angle iron, cooking pots, theodolite, radio, axes, cement, spade and

so on dictated a maximum walking time of a week or so before resupply was

needed. Therefore one or two airdrops were planned for

all the longer climbs.

Airdrops

Most

of the airdrops were flown by STOL Air, Port Moresby, and Missionary Aviation

Fellowship at Tari with excellent accuracy and results. All mountain flying was

done in the early morning, taking off at first light, officially 20 minutes

before sunrise, and completed by about 10am before the daily build up of cloud

around the high peaks.

Flying

mostly in high wing Cessnas, C180 and C182, with the right

hand door and rear seats removed, the cargo was stacked behind the front

seats, secured in bundles of 30 to 40lbs. A pusher-out, alternately the

surveyor (when the technical assistant was on the ground leading the beaconing

party), or the technical assistant (when the surveyor was the recipient on the

ground), sat in the right hand front seat. On

approaching the mountain, the pusher-out climbed around the seat into the back, an operation fondly called ‘a white knuckle

exercise', and sat opposite the open doorway with feet against two or

three items of cargo. On the pilot’s command “Drop” he pushed the cargo out then

leaned out the doorway to report on the accuracy, in preparation for the next

run, As the pilots accumulated experience most drops landed within 50 metres of

the mark.

The

Cessnas dropped about 400 to 500lbs at 12,000ft. The use of oxygen above 10,000ft,

mandatory for pilots in Australia, was universally ignored in PNG except for

helicopter pilots landing above that altitude.

On

the ground, the dropping target, a 20ft cross of white cloth, was placed

wherever possible on the lee side of a ridge about 50 to 100 metres below the

top. Approaching drop time a smoky fire was lit for

the pilot to find the mark and to track into wind. The packages would then land

on the uphill slope square to the surface without rolling or bouncing, and,

with 50 people watching where everything landed, there were virtually no

losses. In an early experimental drop, a tightly sewn bag of 40 lbs of rice and

tins of meat inside a loose bag, was dropped from 1,000ft at Jackson’s Airport

and the inside bag remained intact. Also it was found

that dropping packages onto a level surface at a low height would cause much

damage and loss. Some pilots confused an imagined need for pinpoint accuracy

with the effect of packages landing at a high forward speed.

As

the air dropping technique improved other heavy unbreakable items were included

– crowbars, guy rods and steel pickets for the beacons, and cement for the

ground marks, wrapped tightly in a truck inner tube wired at both ends. Two

unwanted incidents occurred at Mt Suckling when two crowbars landing on a soft

patch and penetrated five feet into the ground, and a package of cement caught

momentarily on the aircraft's undercarriage, landing slightly long then

bouncing over the ridge and 1,000ft down the other side. It was a couple of

hours climb for a man to retrieve it.

One

airdrop had to be carried out by a local airline with no Natmap people

immediately available. The heavy packages of steel were deemed to be too

awkward to handle and were separated into smaller items and dropped all over

the open summit of Mt Bangeta with little pieces of rag attached to each one,

many of them never to be found. A replacement set of parts was able to be flown

in the next morning and dropped securely by the usual method. A useful

innovation was dropping a small package with a long streamer attached on the

first run as a sighting target. This was usually a welcome pound or two of

fresh meat.

Access

to the Peaks

There

were no high altitude helicopters in PNG until the two

for Natmap and Army Survey Corps arrived in May 1963 on an Army LST vessel.

There was virtually no road network in PNG and for all the beaconing work until

that time the only means of access to mountain peaks was to fly to the nearest

airstrip and then walk.

Whilst

close aerial examination had been made of the peaks with regard to the best

climbing routes, Mt Bosavi proved that what was seen from the air didn't

necessarily agree with what was on the ground. It had multiple sharp ridges

radiating downwards from the cone of the dormant volcano.

Having

selected from the air which ridge to climb the party reached the heavily

timbered rim of the crater after three days but it was found to be not quite

the highest point. The narrow crumbling lip of the crater could not be safely traversed

along the 1,000ft drop on the inside so it was down to the plains again, climb

the next radial ridge, clear the very large trees to find yet another small

peak to the south east very slightly higher. At this stage I developed chicken

pox, contracted during a home stay at Tari a couple of weeks before. Being

highly contagious and potentially serious, this prompted erection of the beacon

at that point, luckily with clear sight in all directions except a narrow

sector to the south east.

One

of the longest walks was to Mt Victoria, about 30 miles in a straight line from

the coast and required 56 hours of climbing. The route taken to each

mountain peak was recorded by compass bearings, walking times for loaded

carriers, and altimeter heights. The local practice when approaching a steeply

falling watercourse was to climb down from the ridge to the crossing point then

up the next ridge rather than following around the contour to a crossing at a

similar level. This latter method would have entailed longer distances along

very steep, slippery side slopes and it was soon recognised that the carriers

knew better. The net effect was that the total climb far exceeded the height of

the peak above the starting point. Mt Victoria was a prime example, requiring 23,000ft

of climbing from sea level to reach the 13,000ft peak.

In

addition to the well known difficulties of climbing

and safely descending steep, bare slopes of smooth clay in the rain, another

significant challenge was the crossing of mountain streams. Fed by daily rains

they ran swiftly and deep, crashing over slippery rocks and fallen trees. To

cross safely with a load required felling of one or more trees, sufficiently

long and close to the bank to lodge firmly on the opposite bank. Losing some

cargo would be one problem, losing a man would have been a major setback to the

program. A vital asset for the party leader was the well

chosen pattern of steel grips on his boot soles to contend with all

manner of unpredictable surfaces, particularly those of a wet, slippery tree

trunk. The carriers managed with amazing skill, usually in bare feet.

Even on near vertical climbs, requiring the use of hands, some carriers still

persevered with carrying two loads on a pole, one man at each end.

One

hair-raising incident on the walk to Mt Victoria occurred when crossing the

Wami River. The boys dropped a tree across, the branches lodged in the opposite

bank and everyone started to cross. I had just put one foot on the opposite

bank when the branches let go and I quickly pulled the other foot up. There was

a mad rush downstream to catch the blanket bags etc that were floating away but

of greater consternation was when one boy was found to be missing. A hasty

search located him amongst the branches of the tree, now stationary again,

still clutching the theodolite tripod but with his face just above water. There

was much clapping and cheering at his reincarnation, and then work started to

cut down a longer tree.

At

about 10,000ft, towards the tree line, an unexpected factor was bamboo grass.

From the air and on aerial photos it looked like smooth grass and easy walking

but in fact was a dense, deep forest of bamboo

runners only a few millimetres thick but 10 or more metres long, impossible to

walk through and very difficult to clear. Every stroke with a bush knife

required holding a bunch of runners with one hand and cutting with the other

resulting in very slow progress.

During

the climb to Mt Victoria an unusual situation arose. Due to the influence of

two different branches of missionary activity some of the 50 carriers

stipulated observation of their Sabbath rest day on Saturday, while others

required their Sabbath on Sunday. One of these days was used for an airdrop but

it lengthened the climb to ten days. After several days at 13,000ft in freezing

temperatures, violent storms and rain the Sabbath became less important and the

return journey took only five days. A mudmap explanation before the event of a

total eclipse at 9 o’clock one morning may also have influenced the carriers’

view of divine warnings and claims of Godly power they had received.

On

some stretches the carriers were able to hunt for game. On the climb to Mt Suckling

a track cutting party of four carriers and one policeman returned to camp one

day with 200lbs of fresh meat.

During

each climb it was mandatory for the beaconing party leader to provide medical

attention for the carriers and about an hour was set aside for this each day.

As the country became rougher, cuts and bruises were most common and the

afternoon line-up for attention became known as the ‘iodine parade’. A one gallon plastic bottle barely lasted for the length of

the trip. If illnesses occurred it usually required the man to be sent down

with a companion to help.

On

high mountains, over 12,000ft, the carriers usually camped at the tree line, at

about 11,000ft, where there was some shelter and firewood. Thirty or so would

go to the summit each day for a bonus payment above their normal wages and work

to erect the beacon and build the cairn.

At

the conclusion of the beaconing all the carriers would return to the Patrol

Post and hand in their personal gear and receive payment for their labour.

Usually 30 to 40 carriers would complete the whole journey, with the others

being used mainly in the initial stages.

In

newly contacted areas such as Kukukuku country a Patrol Officer was required to

accompany the party but the newly recruited people were invariably excellent

workers. People from remote areas were, generally speaking, not only

excellent workers but good companions. Nearer to the bigger towns

things were not always so easy as people from those localities had heightened

monetary expectations since seeing the introduction of western culture and

values.

Equipment

used by Beaconing Parties

Additional

to items previously mentioned, the following items were essential for the

beaconing parties:-

A510

radio, a small portable radio in two packs totalling about 10kg, on loan from

Army, worked very well. There was no regional network of repeater stations as

required by present day pocket sized telephones. It

required a dipole aerial 20 metres or so long to be strung up in trees and used

a 90 volt battery which did not hold its charge well

in high humidity. It did have the major advantage of having plug-in crystals

providing access to the telephone network and to civil aviation control tower

frequency for talking to aircraft during airdrops.

Light-weight

plywood boxes with a watertight lid. These were intended to be carried on a

wooden pack frame but often appeared after the first day tied two on a carrying

pole. These replaced the standard steel patrol box, one metre long,

traditionally used by Patrol Officers, which were difficult to handle on near

vertical climbs and descents.

One

small, one-man, metal box, lockable, for money, trade tobacco.

6

metre rolls of plastic for waterproofing carriers’ tents, which invariably

leaked copiously; also useful for collecting rainwater for cooking when not

near a river.

Large

cooking pots for rice for 60 plus people.

Other

standard equipment included:

Tilley

pressure lamp for night work which the boys, amazingly, could carry in its

wooden box for two weeks without breaking the mantle

Steel

frame stretcher, able to be used for sleeping on a steep slope with two boxes

under the downhill end, one box in the centre, and for sleeping in mud.

One

non-standard item which appeared on the walk to Mt Victoria was made from two

strips of truck inner tube and a piece of wire borrowed from the beaconing

gear. One of the carriers, on a break from his regular job of drydock diver in

Port Moresby, fashioned a spear gun, produced his diving goggles and sank into

the river where we were camped. In fifteen minutes he

came up with a welcome feed of three large fish.

Construction

of the Beacons

Beacons

were made from two 7ft long square steel pipes telescoped together to make a

14ft high target. The four vanes were 4 x 2ft, heavily galvanized and painted

black. Guys were four steel pickets bolted to the centre pole and sloping

outwards through the cairn to steel pickets driven into the ground and four

long steel rods jointed at about 5ft intervals from the outer edges of the

vanes down to turnbuckles fastened to steel pickets. The turnbuckles were

locked with steel rod passed through and u-bolted to the guys. The poles and vanes

had to be carried but everything else could possibly be airdropped. Each beacon

was assembled in Port Moresby before despatch to check for completeness, bolt

hole sizes, then dismantled, painted and packed.

Where

topography and rocks allowed, the cairns were 12ft diameter about 8ft high.

This required two to three days digging and carrying for 40 men, very hard work

at high altitude. The largest rocks were placed around the base and had to be

rolled into position. Hundreds of cairns built throughout Australia were made

with sedimentary rocks, flat sided and able to be built with stable vertical

sides. PNG igneous rocks were invariably rounded and the cairns had to be

conical, not least to withstand occasional earthquakes.

Each

beacon had three recovery marks outside the cairn, one suitable for an

eccentric observing station. It was hoped that any subsequent users would

occupy the eccentric mark and not interfere with the cairn. However, in recent

times an unconfirmed story said that the beacon on Mt Victoria was demolished

to make way for a communications tower, even though there was a very slightly

lower peak a couple of hundred metres to the south east! Also heard was news

that some cairns had been demolished to gain access to the ground mark for crustal

movement observations, instead of using the eccentric station.

The

ground mark was a metal pin in a solid concrete block, using quick set cement

usable underwater. The recoveries were concrete, drill holes in rock or steel

pickets, as required. Loose rounded rocks covered with deep soil created some

difficulty in setting stable marks.

The

beacons on Yule and Tafa replaced crosses previously set on the highest points

by Christian missionaries based at Kerema and at Ononge, near Woitape. The

missions had been very helpful in the early reconnaissance by H.A. Johnson and

in the first beaconing work. Each of these beacons was constructed as a

specially made square tower with a cross standing above it.

Observations

by Beaconing Parties

The

aim was always to observe an astro-fix, as positions of most high peaks had

never been observed directly, and then azimuth observation to the next visible

beacon, if any. A 360 degree round of photographs were

taken for annotation with names and confirmation of intervisibility, and

barometer heights recorded using three aircraft altimeters.

A

typical weather pattern was cloud by 10am, rain mid afternoon, storm in the

evening, sometimes with dangerous electrical discharges then clearing by about

midnight. Astro observations could then start but were often not completed in

one night. Beacon and cairn building would then carry on from an hour or so

after dawn and the carriers would be sent back down to their camp as soon as

the afternoon rain was imminent. Depending on the availability of suitably

sized rocks, this took about three days.

Lightning

strikes were dangerous, sometimes coming out of a flat layer of black cloud

with no storm in progress. On one calm afternoon on

Wamtakin, a discharge hit a metal tent pole a few feet from where the surveyor

was standing. During later occupation by an observing party a flash hit the

radio aerial while an observer was talking, discharging through the metal

microphone he was holding and jumping from his ankle to earth, leaving a small,

slow healing RF burn. Luckily there were no serious incidents. Volcanic gas was

also a danger. Near the summit of Mt Yelia Guy Rosenberg lowered a thermometer

into a fumerole to obtain a temperature reading for the government

vulcanologist. He inhaled gas, became unconscious and was pulled out of the

hole by his accompanying policeman

Peaks Beaconed (refer list on following page)

During

the three year period from 1962 to 1964, beacons were

erected by parties led by members of the PNG Department of Lands, Surveys and

Mines and by the Division of National Mapping.

Based

on this work the geodetic observation teams were able to commence in June 1963.

Working alongside the Supervising Surveyor, H.A. Johnson, my role evolved into

organising the deployment of observers, equipment and aircraft throughout PNG

as well as participating in the observations and measurements. This role

continued until the end of the survey in 1965.

|

PEAKS BEACONED –

1962 to 1964 |

|||

|

Organisation |

PNG

Department of Lands |

|

|

|

Height

(ft) |

Name |

Survey

Officer |

Walk in from |

|

1,060 |

Aird

Hills |

|

|

|

5,196 |

Favenc |

|

|

|

14,330 |

Giluwe |

|

|

|

11,889 |

Guruku |

|

|

|

12,392 |

Hagen |

|

|

|

11,369 |

Ialibu |

|

|

|

8,428 |

Karimui |

|

|

|

11,966 |

Michael |

|

|

|

7,395 |

Murray |

|

|

|

10,023 |

Obree |

D

Foley |

|

|

11,634 |

Otto |

M

Erben |

|

|

11,990 |

St

Mary |

D

Foley |

|

|

11,770 |

Strong |

M

Erben |

|

|

14,793 |

Wilhelm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

National

Mapping |

|

|

|

13,090 |

Albert

Edward |

G

Rosenberg |

Woitape |

|

10,755 |

Amungwiwa |

D

Cook |

Edie

Creek near Wau |

|

13,520 |

Bangeta |

G

Rosenberg |

Kabwum |

|

7,863 |

Bosavi |

D

Cook |

Bosavi

U F Mission |

|

11,704 |

Doma |

D

Cook |

Heli

up walk down to Tari |

|

12,851 |

Finisterre |

D

Hutton |

Helicopter |

|

11,887 |

Karoma |

D

Cook |

Betege |

|

11,669 |

Piora |

D

Cook |

Wonenara |

|

9,030 |

Shungol |

G

Rosenberg |

Zenag |

|

9,460 |

Simpson |

D

Cook |

Rabaraba |

|

12,061 |

Suckling |

G

Rosenberg |

Safia |

|

8,861 |

Tafa |

D

Cook |

Woitape |

|

13,240 |

Victoria |

D

Cook |

Kanebaba

Brown River |

|

8,320 |

Vineuo |

G

Rosenberg |

Diodio |

|

|

Goodenough

Is. |

|

|

|

11,756 |

Wamtakin |

D

Cook |

Heli

up walk down to Telefomin |

|

11,104 |

Yelia |

G

Rosenberg |

Menyamya |

|

10,750 |

Yule |

H

A Johnson |

|

In the following section John

Allen’s experiences in undertaking geodetic observations at some of the

beaconed points are recalled.

Arriving

to start the work – May to September 1963

The

privilege of being chosen to be part of the PNG geodetic observation team was

not lost on the five young men who flew into Port Moresby in May 1963. This was

new territory for them, and although they had sound technical experience in

geodetic work within Australia, the prospect of applying that knowledge in such

a formidable landscape as PNG was somewhat daunting. The youngest member of the

party, Ian Johnson, a newly graduated surveyor, had been asked by the Director,

B.P. Lambert, if he was sure that he wanted to be part of the group as “we may

not come out of this unscathed”. But it was the sense of adventure that

propelled the enthusiastic party forward, even though much was still unknown of

the demands and risk of the work.

The

five were Davey Hutton, Ron Scott, Ian Johnson, Brian Campbell and John Allen

and they were warmly welcomed by David Cook and Guy Rosenberg who were relative

veterans, having achieved much in the two years they had been in PNG. Dave in

particular, as the most senior officer next to H.A. Johnson, inducted the new

arrivals into the steamy, tropical surroundings that were so different to the

arid conditions of Australia's deserts where much of the new arrivals’ previous

work had been located. In the month or so before they were moved to their first

mountains they needed to understand the culture within

the country that was governed by the Australian Administration, and the totally

different culture and language of the local people. (Pidgin English was spoken

by the national people in areas where expatriate contact had been made, but in

more remote areas, tribal language predominated). We found David's knowledge

and expertise was invaluable.

Lifestyle

in the more remote areas was totally different to the relative sophistication

of Port Moresby and the other major towns, and because the survey teams were

going to move through the length and breadth of the country it was necessary to

be acquainted with as much information as possible. Even information about primitive

superstitions and Cargo Cult beliefs was to be useful.

Other

information that related to recent history was quickly absorbed, for even in

Port Moresby Harbour there were still many remains of wartime activity. The

most touching, however, was the visit to Bomana War Cemetery just outside Port

Moresby where more than 3,000 Australian graves are testament to the fighting

that occurred in the surrounding region, which included the nearby Kokoda

Track. Even more sobering and poignant was the sight of so many headstones that

gave the ages of those killed to be much younger than even we were, and our

average age was only 25 years. It put into context why we were there, and at

that time, the country's security and defence was probably a higher priority

than economic and social development.

Helicopter

Training

One

of the most important aspects at which we were all required to be proficient

was that of the operational procedures for the helicopters that were to be so

vital to the success of this survey. Two Bell G3B1 super-charged helicopters,

the first of their type to arrive in Australasia, were chartered from a Sydney

company, Helicopter Utilities. One was to work with the Royal Australian Survey

Corps in their coastal survey, and the other was assigned to the Division of

National Mapping. They arrived at Port Moresby on 21 May 1963 and two days

later the Natmap chopper, carrying two pilots and H.A. Johnson landed on the

summit of Mt. Victoria at an elevation of 13,240ft. The success of this flight

confirmed the choice of such aircraft for the survey and it also foreshadowed

the revolutionary change that was to occur to aerial transportation in PNG.

During

the geodetic survey as we travelled through the country there were many

opportunities to demonstrate the versatility of this new form of aircraft, and

although the main purpose was always to fulfil its prime survey mission, its

capabilities were promoted whenever possible. The purpose of encouraging and

educating PNG Departments and others in the use of these helicopters was

ultimately to be to the benefit of Natmap, as the very high cost of contracting

this aircraft could be shared by others. Right from the outset an attempt was

made to do this.

The

training that we were required to do as passengers/crew members on the

helicopter had no preparatory prescribed reading; it was a matter of learning

on the job. The pilot sat on the right side of the cockpit and we sat on the left hand side or central position if required. All of that

seemed pretty straight forward but then it became more challenging. As

some peaks did not have suitable landing areas for the helicopters, we were all

required to be able to descend a rope from the hovering helicopter and

establish a landing pad.

The

prefabricated landing pad consisted of six lengths of heavy timber and this was

transported under the helicopter by means of a cargo hook and sling. When the

timber was released two people climbed down a rope and, while the helicopter

waited at lower level with the pilot keeping an eye on the weather, the pad was

quickly bolted together, secured with wire to steel pickets and the site

cleared of any bush that had grown up since the beaconing party left.

After

we had gained confidence in descending from the hovering helicopter, practised

at a height of 50-60ft using a Sky Genie descent device to lower ourselves, a

demonstration of the chopper's capabilities was arranged at Murray (Army)

Barracks. Invitees of various departments and a lot of interested locals came

to see the helicopter's carrying versatility and were shown the cargo sling

suspended below, and how cargo could also be transported on the two external

carry racks that ran down each side of the machine. To demonstrate a couple of

us were strapped on either side, and a low circuit was flown without any of us

falling off.

Then

to cap off an interesting afternoon, it was decided to show a member of our

party descending from the hovering helicopter. Guy Rosenberg had been a French

Paratrooper before joining Natmap and he was willing to make the descent. To

make an impressive show, the length of the nylon rope that we were using

decided the height at which the chopper would hover. So

from about 200 feet Guy proceeded to free fall until about 50 feet from the

ground when he applied the friction brake on the Sky Genie. The abrupt stop in

mid air created such a force on the chopper that we could almost see it bounce

in the air as the pilot applied control to prevent it being plucked out of the

air. Within seconds though, Guy was gently lowering himself to the ground

amidst much applause. It was later noticed that the half inch diameter nylon

rope was almost burnt through at the point where the friction brake was

applied.

This

episode occurred shortly before we left Port Moresby to move to the first

mountains. The time we had spent in Moresby preparing and checking our

equipment, and getting used to our new surroundings was invaluable as we had

also developed a strong camaraderie and confidence in each other that was to be

essential as we worked together as a team. The opportunity at Murray Barracks

to display a little of what our future work entailed was very satisfying, as

everything that we were to do hereafter whilst on the mountains would only be

known to ourselves and recorded in our survey records.

Moving

to the Mountains

The

first two mountains to be occupied were Mt Yule and Mt Strong. Ron Scott and

Ian Johnson went to Yule and Brian Campbell and I went to Strong, but first we

were flown by light aircraft to Tapini, just to the north-west of Moresby. This

was the base from which the chopper would operate as it ferried in about five

loads of equipment to each of the mountains. We had to wait there a few days

before we were able to be flown in. During that time

we were able to see a different PNG to that of around Port Moresby and we were

able to get a bit of an idea of how to interact with the local people.

Our

host at the guest house where we stayed was a much

experienced expatriate who had actually been the District Officer for

this outpost before he transgressed. He had been found guilty of being

overzealous when he chained one of the local men to the flagpole; this man had

paid little regard for the custom of gathering with the rest of the villagers

for the daily early morning flag raising ceremony. I'm not sure how long the

local man was chained there but the District Officer was given three months

jail and dismissed from the service. Nevertheless he

had sufficient sway to be allowed to remain at Tapini and he developed a nice

little guest house that became a popular spot for people wanting a short break

from Moresby. (Tapini was about 3000 feet above sea-level and was cooler and

didn't have the high humidity that was common to coastal areas).

When

the helicopter flew in it created much excitement amongst the local people and

this became even more so, for while waiting for the cloud to clear on the

mountains, the helicopter was used to transport a cow in the suspended sling to

some new pasture.

Mt

Strong – 11,770ft

There

couldn't have been a better mountain at which to commence work than Mt. Strong.

In some ways it was surprising to step out of the helicopter onto a large,

flat, well grassed mountain top that resembled the much lower hills in Australia,

but the elevation was nearly 12,000ft and provided spectacular views to other

trig points some more than 100 miles distant. However, the nearer Mt Yule, only

20 miles away, was our first trig to connect to and that would also be a test

of some of our operating procedures that were developed for PNG.

But

first we had to set up camp and organise ourselves for our stay of nearly two

weeks.

We

erected our two 8 x 10ft lightweight tents in a sheltered hollow about 200

yards from the trig. We set up one tent for sleeping, our two

way radio and technical records. The other one was for cooking and the

storage of food, personal gear and small technical equipment. Out in front of

the tents we spread a plastic sheet to collect rainwater.

The

tents were made of waterproofed japara silk, and although the material was not

much thicker than a handkerchief, it was remarkably effective. During cold wet

windy weather you felt quite secure and safe,

ironically during sunny periods the heat was trapped inside and it then became

too hot for comfort. The floor space of the tent was just sufficient for our

camp stretchers to be set up, one against each wall, with a narrow isle

between. We were supplied with two sleeping bags, where one was placed inside

the other to maximize the thermal insulation, a waterproof ground sheet that

was used as a cocoon around the sleeping bags, and a rubber inflatable

mattress. There was no floor to the tent, which helped when during a torrential

downpour, the water could just run through the tent and escape at the other end

as it did quite frequently on Mt Victoria.

We

kept very little else in this tent except for a few personal items, the field

books containing our observations and measurements, and the radio we used for

our regular wireless “skeds”. Each day we had regular radio contact with the

other parties and also with H.A. Johnson who closely monitored our progress.

During certain times of the day it was always great to tune into Radio

Australia and hear the news. Another important role for the radio was to

provide our time checks, before and at the completion of any astro observation.

One small but important item that became the bane of our lives while we

attempted some of these astro observations was our alarm clock. We were all

committed to doing our utmost in completing the full array of observations and

measurements at each trig point, and some of that work had to be done in

conjunction and reciprocally with others at another trig. The most important

and difficult astronomical observation was the simultaneous reciprocal azimuth

using the star Sigma Octantis. The challenge for us was to try and achieve this

whenever possible. When such an opportunity arose, parties at each trig would

arrange a radio “sked” to ascertain the weather conditions prior to the

commencement of the observation. If there was a difficulty for one or both

parties because of cloud, then a second attempt would be made two hours later.

Progressively throughout the night, starting as early as 7pm, two hourly checks

would be made until about 11pm.

Then,

after collapsing into bed, it seemed as if no time at all had elapsed when the

alarm would ring for the 3am check. The hope was that the early morning

atmospherics would cause any cloud that had settled on the peak overnight to

sink to lower levels before rising again as the sun heated the cloud mass and

it collected around the peak again. It was not uncommon for the cloud to clear

at one mountain but to stay in place at the other, thus rendering the attempt to

failure for that evening. On many occasions, when night after night of

disappointing and frustrating attempts to complete this observation in freezing

and muddy conditions, the reaction to the alarm, from sleep deprived party

members, was to hurl the clock far off into the distance. However, frustrating

though it was, everyone stuck to the task, and success was achieved and the

horizontal angles were strengthened through these simultaneous reciprocal

azimuths.

At

the trig itself we selected the eccentric mark from which we would make our

observations, erected the observation tent, and placed the Wild T3 tripod in

position.

Other

technical equipment; the MRA2 Tellurometer and tripod, helios and signal lamps,

12 volt batteries and battery charger and petrol were

left close to the trig and were protected from the weather with plastic

sheeting.

Our

technical procedures for the observations and measurements were identical to

those used in Australia; the weather was the uncertain factor and sudden

changes could occur quite rapidly. For example, during tellurometer

measurements it was necessary to take psychrometer readings to measure the

relative humidity and then apply atmospheric corrections to the distance

measured. It was not uncommon to commence the tellurometer measurements in fine

conditions but then have such a deterioration with cloud, thunder and lightning

in the immediate vicinity that you were concerned for your safety. Added to

that, if you were holding aloft the highly polished chrome psychrometer to take

those wet and dry bulb readings, it seemed as if you were just challenging fate

in providing a wonderful lightning conductor.

A

couple of events at Mt Strong caught us off guard. One afternoon we were

surprised to see coming toward us a group of about twenty men. They carried

bows and arrows and were dressed in typical native attire of bark belt and

strategically placed clumps of grass. It seemed that they were a hunting party

and although they were not threatening, this was our first contact with such a

group. There was an older man who came forward to introduce himself. He was

dressed a little differently in that he wore an Australian army battle dress

jacket that had been liberally waterproofed by layers of pig fat. Although we

were very limited in understanding Pidgin English, he asked me if I could give

him change. He produced from an old wallet that he carried in his jacket pocket

a small corner of a pound note. In keeping with everything else about the man,

the small piece was very scruffy and dirty. At first I

thought he was having me on, that he was the comedian in the group, but I

realised he was serious and expected to get an appropriate response from me. So

being a bit of a joker myself I turned away from him, and from my wallet I extracted

a newish pound note and tore off a corner, similar to the one he offered me.

There was stunned silence when I offered it to him – it was not the smartest

thing I could have done – but after a few seconds there was great

laughter from the main group and I was much relieved. They stayed with

us for an hour or so as we showed them around, not that they understood

anything, and they showed us their hunting skills as they speared a small bird

in a bush.

This

little episode had a sequel when a couple of days later I was finishing some

horizontal angles up at the trig. It was quite early in the morning and through

the theodolite I briefly saw in the foreground the inverted shape of some

moving figures. I remarked to Brian my booker that we could have some visitors

for breakfast. A short time later after we had packed up and returned to our

tents we discovered that the visitors had in

fact been running away, taking with them some of our food. Although it was

theft, my reaction was that it was probably appropriate payback for the game I

played with them earlier. As we were near the end of our work it wasn't

necessary to fly more food in and we managed on the little that had been left.

We

were on Mt Strong for about a fortnight and completed the following observations

and measurements:-

Almucantar

observation for longitude

Circum-meridian

observation for latitude

Simultaneous

reciprocal azimuth to Yule

Horizontal

angles to Yule, Amungwiwa, Bangeta, Albert Edward, Victoria and St Mary.

Simultaneous

reciprocal vertical angles to Yule, and Albert Edward

Tellurometer

measurements to Yule and Albert Edward

Mt

Victoria – 13,240ft

After

a short time back at our base in Port Moresby we were ready to occupy Mt

Victoria. Waiting on Mt Albert Edward were Ron Scott and Guy Rosenberg and they

were eager for us to make the connection to them as that would then allow them

to complete their work there.

Our

flights into Mt Victoria were from Murray Barracks in Port Moresby and only

took a little more than 30 minutes to fly in from sea-level to the summit at

13,240ft. Brian Campbell took the first flight in, and there was another three

trips with all our gear before I was to take the last, but unfortunately bad

weather prevented that final trip from getting off the ground. Cloud and poor

conditions prevented the final flight getting in, but three days later it

seemed that there was a good opportunity to make that trip and we started off

confidently.

Captain

John Arthurson was a most assured and safe pilot and he knew how keen we were

to get this trip completed. As we approached the peak

we could see that swirling cloud had commenced to gather, and so instead of

approaching from the south western face, John flew around the top to see if a

better landing could be made from the east. It wasn't much better and so he

backed off a bit to get a better appreciation of the cloud build-up. Although

our ground rules were that under no circumstances was a landing to be made

other than at the helipad, John was aware that on the eastern side a flat rock

shelf only 300ft lower than the summit was suitable for landing. As we headed

for that rock shelf the chopper was caught in a sudden downdraft and we must

have dropped 30-40ft in an instant before John was able to recover. I looked

across at him and he was as white as a sheet; any closer to the side of the

mountain would have been a disaster. We were now close to the rock shelf and

John landed there and within a few minutes I had unloaded my gear and John was

on his way back to Moresby.

Up

on the peak, Brian had heard the chopper flying around but knew when it pulled

away that he would have another day by himself. He was amazed when about an hour

later I pulled aside the tent flap opening and came in out of the cold. Whilst

he was pleased to see me he hadn't been very happy during the past few days and

was debating whether it was all worth while - he had a brother working in

Moresby and had seen the relative ease and comfort the expats enjoyed, and here

he was stuck on a mountain top in often atrocious conditions and getting a

pittance for what was very demanding and dangerous work. He helped me carry up

the remainder of my gear from the rock shelf below and for a while we were able

to concentrate on getting ourselves established in order to make the necessary

connections to those waiting on other peaks. But Brian's feelings didn't

improve and he decided that he wanted to quit.

I

can't recall exactly what happened when I passed the information onto H.A.

Johnson at our base other than he arranged for Davey Hutton to replace Brian.

This changeover occurred the next day and I think Brian was given the

opportunity to rethink his decision but he declined. This default must have

been very concerning for Mr Johnson as it could have been the tip of the

iceberg if others were similarly disgruntled, and would have put the whole

survey in jeopardy. He knew that his people were exposed and stretched on the mountains,

but fortunately this was an isolated case and was never repeated.

Brian's

replacement, Davey Hutton, had a much different personality and his

cheerfulness and good humour was a great asset during the next four weeks we

were on the mountain. Davey was older and more senior to me but as I had

greater astro training and experience, I retained that responsibility.

Davey

was very experienced with Tellurometer measurements and theodolite observations

so we were able to share in those tasks which resulted in more balanced

workload. While at Mt Victoria we received one of the large four

foot diameter Tellurometer reflecting dishes, and this enabled us to

measure with great accuracy distances up to 120 miles.

We

had some small difficulties such as when we ran out of water and had to descend

to lower levels to scoop up enough from rock pools, but generally we had more

than enough rainfall as one of our photos reveals. There were no native

visitors to this trig but had they arrived they would have seen one of the

greatest views in PNG. On a clear night the lights of Port Moresby to the south

west were visible, and to the east you could see out past Popondetta to the

Solomon Sea. Everywhere else the horizon seemed limitless.

Mt

Victoria was the dominant peak in the Owen Stanley Range and it was a great

privilege to have been able to conduct the following observations and

measurements from this majestic mountain.

Almucantar

observation for longitude

Circum-meridian

observation for latitude

Simultaneous

reciprocal azimuth to Albert Edward and Obree

Horizontal

angles to Army Stations AA006, AA034, Albert Edward, Suckling, Obree, Tafa,

Yule, St Mary and Strong.

Simultaneous

reciprocal vertical angles to Albert Edward, AA006, AA034, Suckling, Obree and

Yule.

Tellurometer

measurements to Yule, Albert Edward, AA006, AA033, AA034, AA044, Obree and

Suckling.

Leaving

Mt Victoria we had another fright when, having sent

all our equipment out on earlier flights, Davey and I loaded our tents, bedding

and personal gear onto the chopper's carrying racks, climbed in and sat back to

enjoy the flight into Moresby. Not long into our descent I noticed out my side

door that a tent was starting to unravel from where it was tied. The turbulence

of the main rotor blades combining with the airflow of our rapid downward

descent was about to cause a major disaster if the tent broke free and caught

in the tail rotor. Within seconds John Arthurson backed off his speed and while

virtually hovering many hundreds of feet above the mountain's sloping side,

Davey opened the door and with me holding the belt of his trousers, he lent out

and secured the tent. This was a spontaneous act carried out in self

preservation, and was done through the confidence we had gained during our

training at sliding down a rope at Murray Barracks. Fortunately

an episode like this never occurred again.

A

Short Break and Some New Personnel – November 1963 to January 1964

After

returning to Port Moresby and preparing to go to our next trig there were a

number of events that changed the direction of our work. Our helicopter became

disabled and required a main rotor blade to be flown in from the U.S.A, and

another problem occurred when the light plane that was to fly me to Goodenough

Island, off the eastern tail of the mainland, had engine trouble as it prepared

to take off from Jacksons Airport and the trip was aborted. These events plus

some worsening weather brought about a decision to send the observing parties

back to Australia for a short break.

When

they returned they were joined by Jim Carlisle, Mike

Stevens and David Price, who was to become my booker for the remainder of the

survey. Also, two surveyors, Jim Cavill and Mike Kellock and assistant Merrek

Erben were seconded from the PNG Department of Lands. With the addition of

these people we had sufficient personnel to mount five observation teams, more

than doubling our earlier capacity. The total of 14 people working over the

next two months formed the Natmap's largest contingent operating on the geodetic

survey at any period.

A

change in direction also occurred at this time when, due to monsoon activity to

the south-east, work in that region was halted and the survey resumed

north-west from Yule and Strong toward Mount Hagen.

Mt

St Mary – 11,990ft

We

were flown in to Mt St Mary from Tapini and found conditions very similar to Mt

Strong which was relatively close by. We had a decent camp site close to the

trig and our workload was fairly light.

It

was a good introduction to the work for David Price and he performed well. The

only challenge that he had set himself was to give up smoking, and as there was

no way that he could get supplies he persevered for the couple of weeks we were

there – and to his credit he overcame the habit.

We

had one visit by the local people. Some twenty men and boys appeared one

afternoon soon after we arrived. I expect the sound of the chopper brought them

to us but maybe they had been involved when the beacon was built, but no doubt

the bush telegraph was well and truly operating. It was difficult to converse

with them but their body language indicated that they were very pleased to see

us.

Most

were neatly dressed, unlike the hunting party that had visited us on Strong.

They were very confident and even took the liberty of looking in our cooking

tent where we had our food supplies, amongst other things. Their faces lit up

and they actually rubbed their stomachs in anticipation of sharing some of the

food. We weren't so generous as to do what they hoped for, and later they

drifted off and we didn't see them again, but my response was that maybe this

was an example of Cargo Cult beliefs. From what I had read, many native people

expected that one day white people would come from the sky and land on mountain

tops with all manner of things that would be passed on to the deserving

recipients. Our arrival fulfilled much of their expectations except for the

critical final act of dispersing the goods! Whatever the beliefs of these local

people you had to admire their tenacity, because to reach the summit of St Mary

they would have had to ascend at least 7,000ft from the security of their

village and enter the unpredictable and threatening regions of the mountain

peaks.

At

Mt St Mary we completed the following observations and measurements.

Almucantar

observation for longitude

Circum-meridian

observation for latitude

Horizontal

angles to Strong, Albert Edward, Victoria, Yule and Amungwiwa

Simultaneous

reciprocal vertical angles to Yule, Strong and Amungwiwa

Tellurometer

measurements to Yule, Strong and Amungwiwa

Mt

Bangeta - 13,520ft

Mt

Bangeta is a significant point on the Huon Peninsula just to the north of Lae. It

is at the eastern end of the Finisterre Range and its elevation provides

surrounding visibility of more than 100 miles. Our work was to connect to trigs

mainly to the south. Incidentally, we arrived at Lae shortly after the 20th

anniversary of its capture by the 7th and 9th

Australian Divisions in early September 1943. The resultant pursuit of

Japanese forces across the Finisterre Range and up the Markham and Ramu Valleys

occurred very close to our vantage point on Bangeta.

With

good weather, deployment of the observation parties gathered pace and in just

one day we almost had our party in place on Bangeta. There had, however, been a

change in plans for that day as a request had been received from the Supervisor

of the Lae Botanical Gardens to allow one of their botanists to fly into

Bangeta and collect samples.

It

was decided that the botanist could go in on the second last flight, and in the

intervening period when the chopper flew in the final load, (and me), he would

have about 90 minutes to collect his samples. The good weather was a factor in

making that decision, but unfortunately it wasn't possible to take that last

load in and the botanist wasn't able to be picked up until the next day.

Unbeknown to us at Lae, the botanist had enthusiastically alighted from the

chopper after the 13,000 foot ascent from sea level,

which only took about 30 minutes, and had rushed around gathering all his

specimens. After about 30 minutes he became very ill with altitude sickness and

David Price gave him his stretcher and bedding so that he could recover. It

wasn't until the next day when the chopper arrived that he was strong enough

get on his feet again, and so unfortunately for him, he didn't achieve all he

had hoped for during his time on the mountain.

Fortunately

for us we didn't have problems such as that although we did suffer from

physical exertion when, toward the end of our stay, we had a dry spell and we

ran out of water. Down below on a flat plateau rain had collected in rock

pools. It was however about 300 feet lower than the peak and the effort of

climbing up with a four gallon container of water was

painfully slow. Numerous pauses were necessary to complete the climb, and

whilst one of the reasons was the altitude, another was the fact that our general

health deteriorated whilst on the mountains. This was due to the fact we had no

nutritional understanding of the most suitable foods to eat, and what we ate

were tinned or dehydrated foods that we had chosen ourselves from the

supermarkets or trade stores; a staple food being rice. Through the sparing use

of water – we were well accustomed to that having often rationed ourselves to a

gallon of water a day whilst working in the deserts of Australia - we only

needed to make the visit to the rock pools on two occasions, but our person

hygiene was ignored as water was used only for the essential needs of drinking

and cooking.

At

Mt Bangeta we completed the following observations and measurements.

Almucantar

observation for longitude

Circum-meridian

observation for latitude

Horizontal

angles to Amungwiwa, Shungol and Piora

Simultaneous

reciprocal vertical angles to Amungwiwa, Shungol and Piora

Tellurometer

measurements to Strong, Amungwiwa, Shungol and Piora

Mt

Otto - 11,634ft

The

momentum of the organisation and deployment of personnel became apparent at Mt

Otto as our observing party was placed on the summit before the beaconing party

arrived. But it was only a matter of an hour or so later that a line of about

25 local men were led to the top by the Merrek Erben of the Department of

Lands. He supervised the construction of the beacon and building of the cairn,

and it was most interesting to see this.

His

first major problem occurred when the men were digging up rock to build the

cairn. Not long into this work there was a sudden cessation as crowbars and

shovels were thrown down and the men hurriedly backed away from their

excavation. They had uncovered a crevice in the rock and their superstition

caused them to greatly fear the presence of a mountain devil. Merrek was

quickly on the scene and to put this nonsense to rest proceeded to urinate into

the hole, remarking in pidgin that, “That will take care of him”. His actions

caught us all off-guard and there were howls from the local men and they became

quite agitated. They were about to walk off the job before Merrek was able to

convince them to work from a different rocky outcrop some 200 yards from the

summit. Eventually the cairn was built but not before we were able to witness

Merrek adopting a more diplomatic and persuasive technique with his man

management.

The

supplies that had been brought to feed the local men consisted of rice and

tinned meat. Whilst everyone had been working some tinned meat had been stolen

and although Merrek suspected a certain person, he lined all the men up. He

told them “the food that we have brought here is to feed you. It is not my

food, it is your food, and yet one of you is a thief and has taken what belongs

to you all. You should watch out to make sure that this man does not repeat

this.” The beaconing finished without any further drama and the men returned to

their village, but the incident with the crevice of the mountain devil was not

likely to be forgotten by them.

Our

observations and measurements proceeded normally. The only difference was that

we spent the Christmas period on the mountain, and on Christmas Day snow fell

on Mt Wilhelm as we were completing measurements to the party of Guy Rosenberg

and Ron Scott.

At

Mt Otto we completed the following observations and measurements:

Astro

Position Lines in lieu of Almucantar and Circum-meridian observations

Horizontal

angles to AA050, Piora, Michael, Karimui and Wilhelm

Simultaneous

reciprocal vertical angles to AA050, Piora, Michael, Karimui and Wilhelm

Tellurometer

measurements to AA050, Piora, Michael, Karimui and Wilhelm

As

we finished our work here and were looking forward to be taken down to Goroka,

light cloud formed around the peak. We listened as the chopper hovered overhead

trying to disperse the cloud with the turbulence of its main rotor blades. It

didn't succeed but it was nice to know that every effort was made to get us

off. We were taken off the next day.

Although

we finished our work there, the summit was later visited by the helicopter on

10th January 1964. The reason was for the training of a change over

pilot to relieve Captain George Treatt who was due for a well

earned break. The new pilot had been flying for the Army at lower

altitudes, but there were significant differences with the higher altitude

flying. George had flown the helicopter to the summit and had just changed

seats with the new pilot. As the chopper commenced to rise and was only a

couple of feet off the ground, a sudden strong blast of air destabilised the

aircraft and it fell on its side, sliding down a side slope and ended up as a

write off. Fortunately both pilots escaped serious

injury. One wonders what the local villagers thought about this incident and

any connection with the earlier one when the mountain spirit had been

besmirched.

Mt

Ialibu - 11,369ft

We

flew into the small outpost of Ialibu from Mt Hagen on New Years Day 1964. We

were the first flight out of Mt Hagen that morning as most people were getting

over the celebrations of the night before. As the pilot of the light aircraft

aligned the plane to land on the east-west grass runway, the rising sun created

a visibility hazard as he flew directly into its brilliance but we were able to

see that the runway was not clear for landing. Hundreds of people, we were told

later that there were up to 3,000 men, women and children, were rhythmically

advancing down the runway, festively dressed in bird of paradise plumes, bodies

brightly painted and also anointed with oil, beating drums or carrying spears

and large shields. On that day Ialibu was to be the centre of a huge sing sing.

The pilot must have encountered something like this before as he had no

hesitation but to buzz the crowd below, and as we skimmed over the cowering

assembly, the bird of paradise plumes shook vigorously in the wind. As the

crowd quickly retreated to the sides of the strip and we came into land I was

concerned that there would be some resentment to the pilot's actions, but

everyone was in a festive mood and for the remainder of the day we watched in

amazement at the colourful and entertaining display given by these people.

We

stayed with a young patrol officer who came from New Zealand. Like everyone we

met at the various outposts, he was most hospitable and although he had little

notice of our arrival he shared his limited food with

us and gave us a bed for the night. We were surprised that he had so much

responsibility for one so young but he impressed us with his confident manner.

While there he took us down to a small trade store that was managed by a local

indigenous man, which was fairly uncommon at that time. We observed the man,

when serving a less educated tribal man who needed batteries for his torch, as

he went to the back of the store and took two batteries from his own torch and

proceeded to sell them as new items. Business ethics were obviously one area

that he didn't understand, but probably he went on to be most successful.

We

only had a short stay on Mt Ialabu as soon after we had commenced work, our

helicopter crashed on Mt Otto and it was necessary to bring everyone off the

peaks at the first opportunity using the chopper assigned to the Army. As it

was also approaching the time when the parties were to be withdrawn to resume

geodetic surveys in Australia, all it meant to us was a slightly earlier

homecoming. We had achieved a great deal in the second part of our operations